By Graham Wellstead

Introduction: Delve into a fascinating tale of dedication and innovation in wildlife conservation with our guest contributor, Graham Wellstead. In this blog, Graham shares his personal experiences from the late 1970s, focusing on the challenges and triumphs of breeding and releasing Barn Owls and European Polecats in the UK. Before the concept of rewilding gained popularity, there were pioneers like Graham, whose efforts paved the way for contemporary conservation methods. Join us in exploring this intriguing journey of wildlife rescue and release.

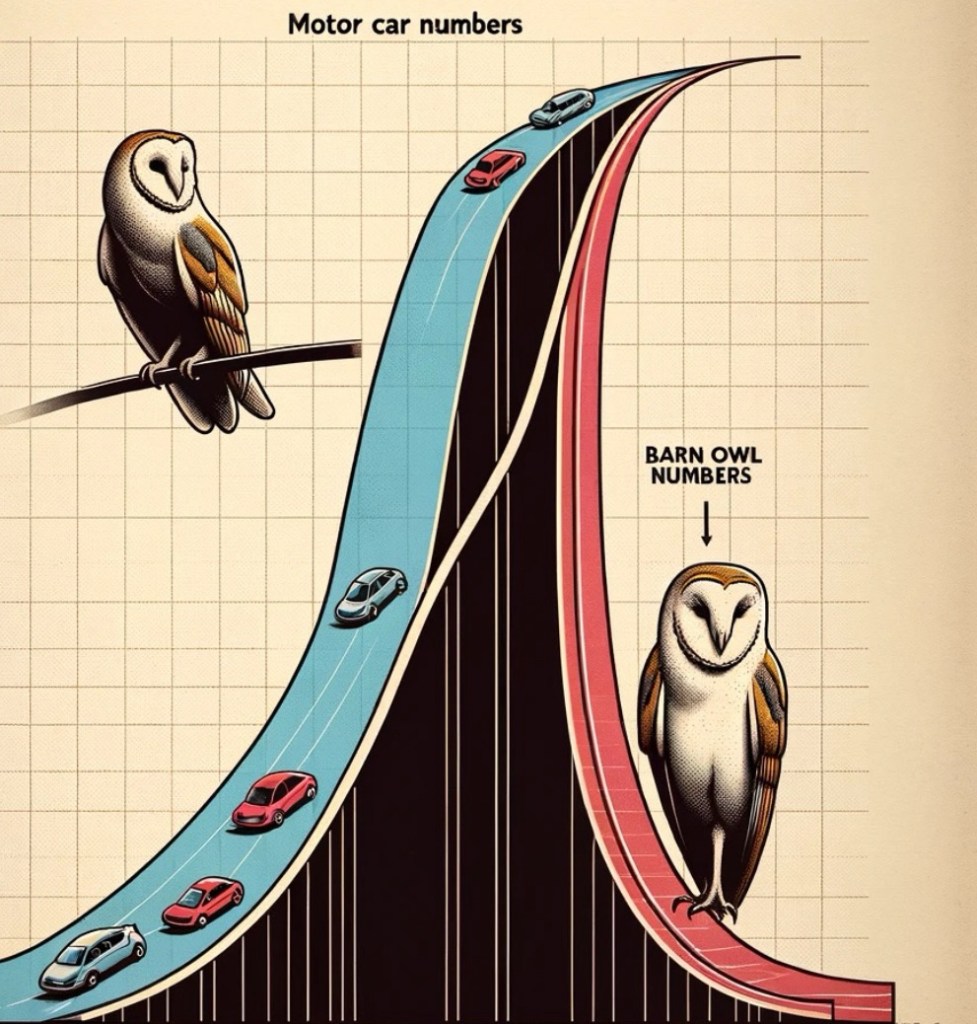

In the late 1970’s I was aware of the decline of two species in which I had a longstanding interest. The Barn Owl Tyto albaand and the European polecat Mustela putorius. When time allowed, and for the Barn Owl, time was, I believed critical. The population was nose diving to oblivion. One of the major causes was the increase in the motor car. A graph would show that the decrease in population coincided with the rise in the car, between 1935 and 1975, forming a cross on the page which was quite dramatic. The population of the owl starting with its high numbers in 1935 shown falling from top left to bottom right, whilst car figures rose from bottom left to top right – In 1935 there were about 475,000 cars and lorries rising to some 28 million by 1975, with an annual increase of around 29%.

Barn owls are not programmed to deal with such a rise. You may ask why and how are they affected. First – they tend to fly over a hedge and drop down as they cross a road, which brings them into fatal contact with any passing vehicle. Or, they perch on a post at the road side, and are sucked off by the vortex air stream left by a passing lorry, into the path of any following vehicle. Over the years I have tended to these victims, and in every case the driver had no time to react.

In my experience, the second most common man-made hazard is the ubiquitous cattle water trough. They step into, what they see as a shallow bath, only to find its deep and they find it impossible to climb out, so drown!

With numbers falling, I was not alone in trying to save the species, but where most releases failed was the young birds, once independent were taken out, usually to farmland, and simply released to fend for themselves. Sadly, this did not work and while 70% of wild born barn owls died in their first year, while 90% of released birds did not survive. Clearly this approach meant nine out ten were released to their death.

By this time, I had already realised that another way of releasing these birds had to be found if they were to live and thrive. In the middle of setting up my entirely independent scheme, I attended at meeting at the Metropolitan Police HQ at New Scotland Yard, also in attendance were a number of senior Police Wildlife Officers, most of whom I knew, due to my liaison with them in my position as Administrator for the National council for Aviculture, running the National Theft Register, officials from the RSPCA and RSPB, and, vitally, the Minister for the Environment. The meeting thrashed out a scheme to licence the release of Barn Owls. A scheme was put in place where the applicants had to provide evidence of the suitability of the release site. Requirements included – a map reference of the site, proof that barn owls were not already on site, proof on an adequate food supply and proof of no major road within two miles. These requirements were very difficult for a single individual to achieve, and the result was few takers, which killed the licence scheme, it not being illegal to release captive bred barn owls into the wild.

Meanwhile I had come up with a system which I believed would work. At the time I was travelling throughout Southern England, and I took time to seek out isolated barns or farm buildings well away from main roads. Once I had found a potential site, I went to the landowner and set out my proposal. Such was the attitude of the farming sector that I was never once turned away.

I was, at that point, breeding several species of birds of prey, hawks, falcons and owls.

I set up 3 pairs of owls on a property away from my home and off we went. You have to beat barn owls apart with a stick (not really) to stop them from breeding. Left to their own devices and given plenty of food, one pair can produce fifteen chicks a year, and continue for fifteen to twenty years. Breeding for sale, soon outstrips your market.

Having found several suitable barns, and made arrangements with the farmers whose land they were on, I used Longworth live traps (very expensive) to investigate the food supply. I have dissected thousands of owl pellets, helped by inmates of Reading Remand Centre where I was teaching – my remit – teach anything you like that will keep bums on seats for 3 hours at a stretch. There are five species commonly found in owl pellets, identification helped by the fact that owls do not digest the bones, but eject them in the form of a pellet, which produces whole skulls, with a species-specific tooth arrangement.

Those species are; field mouse, bank vole, field vole, common shrew and pygmy shrew. We rarely found any rats or identifiable birds in the many thousands of examined pellets – so much for the Rat killing farmer’s friend.

Now the process could begin. I built an aviary inside the building which depended on what was already there. If there was a loft then it was off the ground, failing that a complete aviary was built against one wall, and in every case a window. As young pairs of owls became available, I set them up in their new home, supplied the farmer with several months of food, laboratory mice and culled day-old chickens. Often the barns were invested with mice and the birds were able to catch their own food. This was evidenced by examining the pellets.

Failing this natural food supply the white mice were dipped in coffee to give them at least some colour.

Barn Owls will breed at ten months, which meant birds were going to nest in the early spring. During the build up to breeding the owls had been able to see what as outside, so knew where they were. This was an important failsafe, as once the clutch was complete, usually five, I opened the window, and the male flew free. Bonded to his mate, in as near natural conditions, he soon began to hunt. When all the clutch had hatched the mother also flew free. Out of 25 breeding attempts only one failed due to the male disappearing.

I mentioned earlier that cattle troughs were a hazard, and we toured the fields at the outset to ensure that every trough has a sack firmly fixed in the trough, giving the birds the purchase, they needed to escape. I have little doubt that other animals also benefitted, including hedgehogs another of our endangered species.

In these conditions the owlets grew up a natural, wild birds, as human visits were restricted to a few moments giving food each day, plus checking and ringing the owlets and taking pellet samples. The landowners were fascinated and did much of the work for me. Their excited telephone calls when owlets were seen flying out and returning, made it all worth while.

Barn Owls lay their clutch on alternate days, completion taking ten days, but incubation starting with the first egg. Therefore, the youngest is ten days behind its eldest sibling. In time of food shortage in a wild nest, cannibalism is usual and common. The youngest eaten by their siblings. Nature often appears cruel.

Over six years I operated this system and produced over 120 free flying naturally reared barn owls. My farming friends excited phone calls when their first owlets began to fly free.

Although the method clearly worked, it was never taken up and included in the failed licence scheme.

The European Polecat is a story for another time, with a much harder problem facing me when it came to success or failure.

Graham Wellstead

3 responses to “Breeding and Releasing British Wildlife (Before rewilding became the catchphrase)”

Doesn’t work well for all species. Including invertebrates

LikeLike

Of course it doesn’t work well with many species, something I am well aware of. Perhaps the anoymous responder should try a species that might, and see how they get on. There are plenty to choose from.

Graham Wellstead

LikeLike

I don’t think anyone would belittle your efforts, Graham – and you’re writing about your results in a specific manner – like you say, you’re ’well aware’ it doesn’t work for many species. That wasn’t what you were claiming. Regarding ‘anonymous’ comments – to be fair, sometimes people will show up as having that status because they haven’t created a WordPress account. But you’re right – there are plenty [of species] to choose from! Simon.

LikeLike