By Graham Wellstead.

I was 10 years old when I had my first introduction to nature, both wild and tame.

It was 1947 just two years after the 39/45 war. My father who was a reservist, was called back to the colours before the war started with the result that he was one of the first to come home. United with his family on my 8th birthday the 11th October 1945, and we moved to a new home previously described in an FFON blog, just a month later.

A large garden allowed the production of vegetables, and meat – we kept rabbits and chickens in large numbers, and my father also had budgerigars, their sale helped out with our family costs due to his low wage. However, the cost of their upkeep meant they were only just viable. So, they went.

Meanwhile, (now 1947) local people, knowing we kept birds, brought in an owl, followed in short order by garden birds damaged by cats, most of which quickly died. However, one bird brought in was not immediately identified, but after consulting my ‘Observers Book of Birds” I discovered it was a Sparrowhawk, and probably a male. He had been hit by a car and one wing was broken midway between shoulder and elbow – and fortunately, apart from slight concussion – which I didn’t know, there no other damage. The concussion made him much easier to handle and I knew he needed a splint. But how to to go about it? Divine guidance?

I lived at the front entrance to large convent. I realised the splint had to stiff but light, the bird only weighing about 5 ounces, so I cut and shaped a cereal packet to cover the inner and outer wing, taped it in place, making sure the wing tips lined up, and then left him to settle and recover.

This species is considered, rightly, by falconers, to be the most difficult to train and fly. The essence of falconry is ‘weight control’, and as I was to discover years later, the leeway between flying and dying and be as small as 1/4 ounce. The little hawk had to be fed things he recognised so I scoured the country lanes for dead birds. Blackbirds, blue tits, chaffinches etc were everywhere, and after a few days I managed to introduce him to wood pigeons, which was the main source of food brought to him in the nest. (Male sparrowhawks cannot cope with prey larger than a blackbird, but females major on wood pigeons when rearing young.)

At this stage I had no knowledge of falconry or management of birds of prey. There were no rescue centres and injured wildlife passed to the RSPCA were euthanised. But by searching my local library I found a book on anatomy of animals which told me bird bones were hollow and breaks repaired quickly. After two weeks I removed the splint and was delighted/relieved his wing had set perfectly which meant he could be released.

Two weeks in an old budgie aviary and off he went into the woodland beside the house. I discovered later that life is hard for this small hawk. Many young males do not survive their first winter.

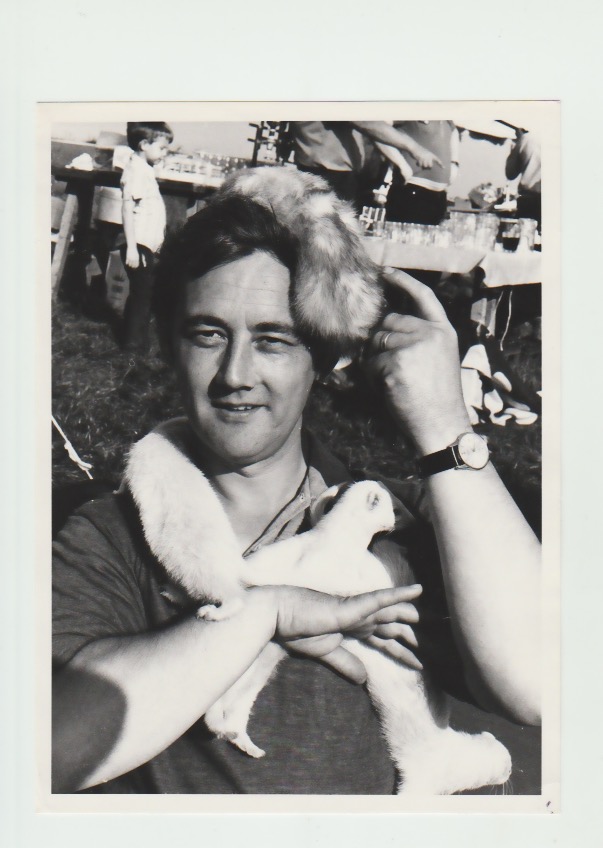

One of my tame robins

The sparrowhawk later became the subject of my PhD and I continued that study over 20 years finding and watching nests, twenty within a 7 miles radius of my home. Their presence indicated by newly moulted feather which I collected. Most the primary and secondary feathers of the female, which moulted during their incubation and rearing period, so were fond close to the nest. Each bird had an individual pattern on its feathers which could be identified year on year. With no interference, I recorded each site and the longest period of a single bird was five years. Breeding with disabled captive birds, something I was possibly the first to do, a pair would breed for at least eight years. Captive breeding at that time was virtually unknown.

Falconry in the 50’s to the 80’s was carried out by very few people. Usually landed gentry or people who had friends in the right places. Birds of prey in the UK were not as widespread as they are now. Peregrines restricted to the high country or coastal cliffs, Buzzards, the west country and Scotland. The most widespread was the kestrel. Hobbies a summer visitor Merlin well spread out on heathland and moorland, but low numbers.

In the late 70’s the government began to work on the Wildlife & Countryside Act, setting out rules and regulations for the care of British Flora and Fauna. These regulations included birds of prey, and all species could only be taken from the wild under a very strict licence scheme. As captive breeding was almost never carried out, I believed the Government and the RSPCA thought that falconry would simply die out. With only about 300 participants in the UK, this could have easily happened. Every hawk eagle and falcon had to be ringed and registered, and every owner was also registered and was given a registration number.

But they did not foresee the tenacity of those involved, and with the establishment of the Wildlife & Countryside Act 1982, breeding began in earnest.

By the late 80’s the Department of the Environment, who monitored both birds and keepers could not keep up with the explosion in the numbers. All but about five species were taken of the list. Two American hawks numbered over 70% of the registrations, and because they were non-native, they were freed of any documentation. They were the Red-tailed Hawk Buteo jamaisensis, and the Harris Hawk Parabuteo unicinctus. Initially their value was high – the biddable and popular Harris fetching £2,000 and the stronger harder to handle Red-tail £1,000. I eventually bred many Red-tails – up to fourth generation, with my last one dying this year aged 34.

Naturally there were a number of ‘get rich quick’ individuals who sought to profit, so took the eggs from their Harris hawks as fast as they were laid. The species, unlike chickens, lays sometimes 3 clutches in a year – up to 12 eggs, but by removing them, the females will lay more – which get progressively smaller. This brought its own problems and many very poor- quality birds were produced. Now there are so many they are difficult to sell. Over the years I have had about ten, and only paid for three. I was never tempted to breed them, but two have been among the best hawks I have ever flown. Having bred Red-tails, when it came to flying a hawk, it was generally that species. Two, mother and son, were very special.

Over the years I have kept seven species of owls, and bred three – barn owls, tawny owls and little owls. Of the seven three were non-native. I have also bred four hawks, and three falcons. One, the Common Buzzard, absent in the wild in my part of the country, had always been the choice for a beginner, but now that has been overtaken by the ubiquitous Harris. While this may be a good thing as the Harris is good hunting bird, and uniquely, can be flown as a group: I have flown six at the same time. In the wild last year’s brood stay with the parents and help rear this year’s babies.

Along with my constantly expanding number of birds of prey, which enabled me to give an in-depth grounding to my students during the 30 years I taught falconry, I also continued with the wild life rescue work. Mostly it was birds, but there were also mammals.

I drew the line at deer and foxes, as I did not have the facilities, but early on I did rescue a litter of badgers, which when found outside the sett with eyes still closed, it could be assumed their mother had probably been killed on a road They were huge fun, a large version of the playful ferrets, stoats and weasels. (Tame stoats and weasels, much hated by gamekeepers, are just wonderful.) As they grew, they became very destructive and I had to house them outside.

Meanwhile my father and I dug an artificial sett in the woods next to the house, and as close to the local common land and adjacent farm. When they were able to forage for themselves and they had made quite a mess ploughing our garden and lawn looking for worms, we released them. Initially with a pen around the sett, which was very successful as that sett as in use for over 20 years – after which I had left home and lost touch.

The first species I had dealt with as a rescue was the Sparrowhawk. It was followed by around 12 others. Most recently, the last bird to come to me, as its time I gave up, was a sparrowhawk female with an identical injury. She was repaired and released on the estate of the college where I had worked for twenty years as a lecturer in environment studies. A fitting end, as the Sparrowhawk was probably my favourite, especially the male. Small and delicate, and a lunatic on stilts if not properly trained, but with a fire inside. I have had a musket spar, at it called in falconry, try to kill a sheep. Musket dates back to the first firearms, when it was said that the hawk left the first like an exploding musket.

Graham Wellstead